On Character |

Yesterday, in an email exchange, an otherwise educated man who supports Donald Trump challenged my evaluation of him as a man of bad character. He asked me who the judge of character is, suggesting that there are questions about how we ought to judge character, and that perhaps my judgment in this particular area is off base.

I thought I’d share my response to that email forum with my Facebook friends.

It’s quite clear to me that the gentleman in question needs more instruction in this area, and it can be given, but it should be mentioned that no human being can acquire a proper understanding of this matter without many years of study and inner questioning.

The word character, before 1333, meant an imprint on the soul. The word is taken from the Greek charaktér, meaning an instrument for engraving, or a distinctive mark.

So the word itself means that which is written in a man’s being. This is a very ancient idea indeed; that our being — our nature, who we are — is a book into which our life writes itself. According to many of the traditions, after death, the angelic kingdoms read that book: so it is essential that we pay attention to what is engraved in us, what our character is.

Whether we believe that or not, life leaves a mark in our being. It is a character, like a letter: a symbol, a representation of what we are. It isn't just defined by the words whereby we describe it; it is described by our actions, by the whole of what we are, which words can point towards but never completely explain. It's in the wholeness of a man's or woman's action and nature that their character emerges, not in any one feature or moment.

As we live, our being is imprinted by that which we take in. It’s true that we begin with an essential core that is independent of external circumstances; but as a man or woman grows through life, they take in a vast range of impressions, which engrave themselves upon their personhood.

This “engraving “ which life imparts upon a human being lies in the deepest part of their psyche, where the impressions are collected and concentrate themselves into their internal (and, consequently) external form of Being.

External behaviors in mankind flow outward through the medium of these collected and concentrated impressions. In this sense, a human being can never be more than what their inner form consists of. Everything they do, every behavior, flows outwardly from it.

The engraving in the being of a man or a woman that takes place over the course of a lifetime tends to follow “grooves” which are etched in the psyche and reinforce themselves. This means that instead of acquiring much new material and constantly learning, human beings strongly tend to engage in confirmation bias and revert again and again to already established tendencies, which are often called habits. Habits are all too often bad for a person, since they frequently prevent new material from entering. (They can be of great use, however, if rightly formed and employed for spiritual betterment.) Over the course of a lifetime, a human being forms buffers, barricades, and barriers which automatically reject new material that differs from what they already believe. Without a determined and intelligent effort to actually see this process taking place and go against it, it is impossible for a human being to undergo further inner development. Consequently, most people end any meaningful inner development in their early years.

Over the course of many thousands of years, mankind has collected wisdom — passed down through the ages — that imparts direction to this process of taking in impressions and forming inner Being. If the process results in a human being who is loving, honest, unselfish, caring towards others, and honors the being of other people, we call the results good; if a person is hateful, selfish, does not care towards others, and behaves dishonorably towards them, we call the results evil.

These ideas of good and evil are not new inventions of my own, but ancient traditions that have withstood the test of time throughout countless civilizations and cultures, both advanced and primitive. The records of these understandings are found in many different texts from many different societies, beginning from as early as mankind wrote anything down.

Collectively, the texts and traditions gathered themselves around the core of what we call the religions. Although religious understandings have been misinterpreted, misapplied, and abused by many generations of people of bad character, the understandings themselves are valid and clear. Human beings, on the other hand, lack critical judgment and always tend towards the evil. Because of this, they prefer to interpret the traditions according to their own whims and vices, rather than attending to the fairly clear instructions encoded in them.

One does not have to be religious to understand the traditions and their implications. Emmanuel Swedenborg made it quite clear, in his books on heaven, hell, and divine love and wisdom, that a human being does not have to be religious in order to qualify for heaven. Even if one chooses to completely discount and discard the metaphysical question of heaven, Swedenborg’s contention is that a human being can be an atheist and still clearly understand that to be loving, honest, unselfish, caring towards others, and honorable towards the being of others is the right thing to do.

This is what builds societies, trust, and value between human beings; and even today it doesn’t matter whether you are a Buddhist or an atheist, it can be readily understood. The moment one lowers one's standard below this, one is already tending towards evil; and human beings make this choice in every moment. One cannot ever stay in the same place; one goes up or down. Without what the Buddhists call mindfulness, or what Jeanne Salzmann calls intention, one goes down. This is a lawful action; entropy affects man’s being just much as it affects matter.

Reading the words and repeating them to one another is not enough. Human beings need to hold themselves personally, from an inner point of view, accountable to the highest possible standard they encounter and can enforce in order to help society and their fellow humans establish right relationships and proper values.

This is the responsibility of a man or woman who wants to live in harmony and intelligent order in relationship to others. It means that they cannot engage in reprehensible behavior where they say hateful things about others or treat them in a hateful way. In the Christian world, it means that they have to treat one another with love and kindness; in the Buddhist world and the Jewish world, the Hindu world, and the Islamic world, it means the same thing. There are few societies where, at the core, the idea that one can say hateful things about others and treat them in a hateful way is considered to be a right thing.

Human beings spend very little time personally observing the way they themselves actually behave, as opposed to the principles they claim to believe in. It’s common for men and women to openly contradict the principles they claim to represent by behaving in inappropriate and inconsistent ways.

It takes many years to obtain a proper education in the grounded philosophical and religious practices that the traditions represent. Ideally, a thinking person needs to not only live through a life which is filled with suffering, trials, and disappointments, but also constantly question their own moral and civic behavior.

They should read a wide range of texts from multiple different religions in order to understand what the traditions teach about human values. If a human being immerses themselves solely in the pursuit of material aims, and believes that their material welfare is the only point of their life, they are quickly consumed by selfishness. This lesson was thoroughly explained by Emmanuel Swedenborg; and it’s quite a shame that modern Westerners no longer read his texts, since the standards he sets for behavior are universal, whether one is religious or not.

Other seminal religious texts of modern and ancient times that are worth reading in order to help establish guidelines for understanding what character means and how it ought to be applied to an individual life include the following:

Christianity:

Meister Eckhart: the complete mystical works

Brother Lawrence: the Practice of the Presence of God

The Cloud of Unknowing

Judaism:

Adin Steinsalz, TheThirteen Petalled Rose

Yoga:

Sri Anirvan: Inner Yoga

Patanjali: Yoga Sutras

Islam:

Ibn Arabi: The Divine Governance of the Human Kingdom

The Bezels of Wisdom

Revelational:

Dante’s Divine Comdey

Emmanuel Swedenborg: Heaven and Hell

Divine Love and Wisdom

Wilson van Dusen: The Natural Depth in Man

Classical:

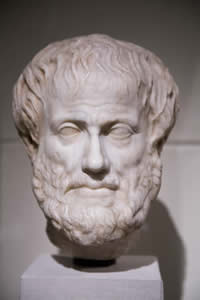

Platos’ complete works

Buddhism:

Dogen: Eihei Koroku (Extensive Record)

Shobogenzo.

Chogyam Trungpa: Cutting through Spiritual Materialism

Of course there are countless religious texts one could refer to in pursuit of this matter, and my shelves are filled with them. I would, however, recommend that one read the above 13 or 14 works in their entirety, carefully, over a period of some time in order to properly absorb their lessons. My extensive reading in this field over the last 40 years have left me with the impression that many of the essential understandings human beings need to acquire can be found in this specific range. I could recommend at least another two dozen books that any thinking person interested in this question ought to read.

For a review of the failure of enlightenment ideology and the progressive downfall of man’s inner understanding, the following books are well worth reading:

G. I. Gurdjieff: Beelzebub’s Tales To His Grandson

William Chittick: Science of the Cosmos, Science of the Soul

For an ongoing dialogue about the need for proper inner understanding in mind, I recommend Parabola magazine, a publication of which I am one of the editors.

Reading is not enough. however.

In order to understand the way that character functions, every person should go to at least one concentration camp and review both its premises and the documentary materials there, to take in an impression of what the ultimate consequences of evil behavior may be. One should travel to the poorest countries one can reach — in my case, India, Pakistan, and Cambodia serve as examples — and spend a good deal of time breathing the air and mixing with the people there in order to understand the consequences of selfishness, the unequal distribution of wealth, carelessness towards others, and destruction of the environment.

Above all, one ought to take in the lessons of modesty, humility, and an understanding of the emotional harm we cause others when we speak rashly or cruelly towards them, treat them dishonestly, bear contempt for their race, religion, or sexual preferences, mock their disabilities, dismiss their legitimate concerns, or bear false witness. It doesn’t matter whether one is religious or not—these behaviors, according to the traditions, are evil ones. Trying to excuse them by claiming it is necessary to act in such a way on a public stand is wrong, no matter who does it.

We should all remember, in the deepest sobriety, that every action we undertake is written in our soul. This is an ancient teaching that is shared by the esoteric branch of Judaism (the Kabbalah) and all of the esoteric branches of Christianity and Islam. Modern students of human character such as Swedenborg and Gurdjieff taught exactly the same thing; and we ignore the lesson at our peril, since the way we are as human beings inside is what really matters about life. Anyone who doubts the deep and ancient classical roots of this premise needs to read their Plato all over again, a second or even a third time. This was the whole point of Socrates’ teaching; and that is why Neoplatonism had such a huge influence on Christianity, not to mention Islam and even Swedenborg’s teaching.

And, as a last note: llike many people, I learned about what character consists of from my mother and father. They are staunch Republicans and never voted for a Democrat at any time in their life, their entire life, until this past election, when my mother voted for Hillary Clinton.

My mother says that Donald Trump is evil.

Others can do as they wish to, but in my own case, I still often listen to my mother, as her guidance, while sometimes unwelcome, has often been good—especially in regards to matters of character.