Following the Development of a Symbolic Thread:

Temptation in Hieronymus Bosch's The Garden of Earthly Delights

How do we know that the artist intended the central panel to be not about lust, a specific sin, but temptation, a general condition of sin?

The presence of naked hordes of figures in the center panel might easily lead one to believe that it has something to do with lust. Nakedness implies sexuality. Yet nakedness more importantly removes all outward signs of rank, profession, and outward activity. By doing so, it focuses on the ground floor of human character — the sensory, sensual, and material nature of the human body and its engagement with its environment. Temptation arises from a fundamental ground of bodily existence, and assumes many guises — only one of which is lust. It seems frankly incredible to believe that an artist of this ability would bother focusing this many figures on a single sin, when there are seven known deadly sins. Following the theory that the center panel is about lust, there would need to be six additional triptychs in order to cover all the essential territory of sin—!.

The premise is even more incredible when we appreciate the fact that the painting deals with large themes; not small ones. Having set the whole universe, divine and temporal, on a single stage, drawing parameters this narrow to define the remainder of the argument would have been ludicrous.

Bosch was actually very specific in indicating that the center panel is about temptation, and he gives us the key in the upper left-hand corner of the panel, exactly where we begin to read it.

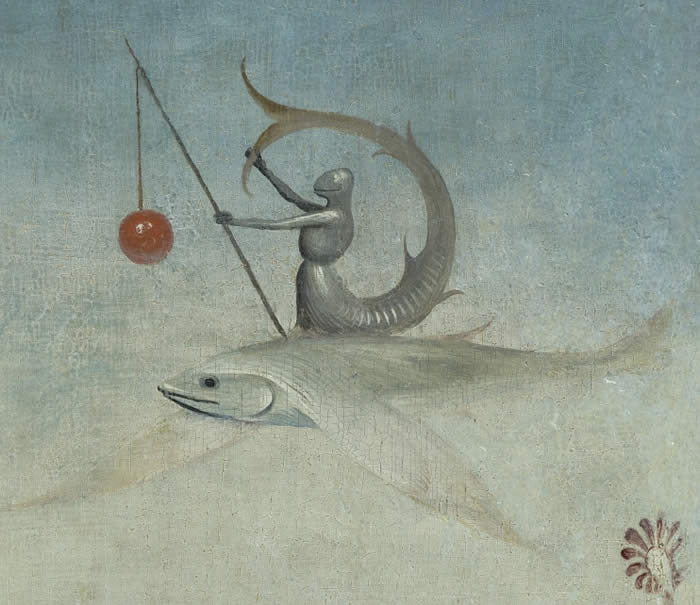

The above scene shows us the Angels struggling for the soul of man; and one of them dangles a cherry on a fishing pole. He is clearly fishing for man; and his lure, the cherry, is what he tempts him with. The artist is making it clear as day in his introductory scene that fruits, in this panel, will represent temptation, and that that is what the whole panel centers around.

In the background of the divine mountain on the left, we see armies sailing out with the same exact fruits, set on the heads of the same exact type of figures. Attempting to arrive at any explanation for this scene other than armies of temptation would be rather difficult, given the introductory scene, unless one wants to egregiously ignore the cue the artist has already given us.

The artist gives us a second and equally important cue here: there are two major classes of temptations to pick up in the painting, blue, earthly, and red, or spiritual. And there is hence a second piece of information to be gleaned here: temptation comes in varieties. The artist assumes we are smart enough to pick up on this, so that when he expands his vocabulary of fruit later in the painting, we'll understand that it begins to represent a greater range of different temptations.

We can directly derive the understanding that red represents spiritual temptation from the fact that the divine, interacting with the earthly, undergoes a transformation whereby its pink tint turns to red. We see this at the top of the earthly tower representing man in the center of the painting. Once again, unless we intentionally ignore the color cues the artist has already established, the conclusion is nearly inevitable.

There are no fruits of temptation in evidence as the Tantric circle in the center of the painting moves towards the back of the painting, where divine influences are stronger. No one has ever explained this before — perhaps it hasn't even been noticed — but the implication is clear enough once one understands the role of the circle. Temptation lessens and even disappears as man moves back towards the divine. The abundance of symbols indicating movement in that direction at the back of the circle, in the center, is again unambiguous. Signs of the influence of divinity abound.

The round blue fruit of temptation — earthly temptation, as we've established by its color and its shared identity with the blue fruit carried by the armies of God in the introduction of the two types of temptation — makes its appearance in the circle at the very moment that it begins its definitive turn away from divine influences and towards the front of the painting.

Fruit is seen at the front of the tantric circle in a number of locations.

In point of fact, the only group of figures without fruit above it, (each in turn representing the ascendency of temptation over man) is the group carrying the egg.

This group precedes the group carrying the pearl with three birds pecking at it, which is doing double duty. Pearls, as we know, represent lies; the distinction between temptation and lying is perhaps moot, since temptations also represent emotional lies about what one ought to do. Here, we glean a suggestion for what Bosch intends eggs, which are not that common in the painting, to symbolize: man is here giving birth to his own temptations, not just the ones God has sent to him. This occurs at the furthest distance away from the divine influence towards the back of the painting.

By the time we reach the bottom of the painting, in the earthly sphere, there is fruit everywhere. No longer playing the symbolic role that's assigned to it in the top two portions of the painting, where it either surmounts figures (representing its influence) or attracts them, the human beings are now interacting with it intensively, and even becoming it. It has furthermore morphed into a wide variety of forms.

What we are seeing in this scene is not lust, but the triumph of temptation, in all its colorful varieties. By the time we reach this level, the artist has been meticulous in establishing what fruit means, beginning with the Angel from the Army of God who dangles it from his fishing rod at the beginning of the panel. If it represents sins of the flesh, it represents all sins of the flesh — not just sexual ones.

There are further sets of inferred social evidences to support this. Sexuality was far from forbidden in the Renaissance; human beings have always been sexual creatures, and the practice is not only accepted, but, generally speaking, enthusiastically endorsed. You can count the famous pieces of visual art in history that openly condemn sexuality on the fingers of one hand, if that. Paintings, even great ones, that openly endorse it are a dime a dozen. Even if lust is, in fact, bad, you're not going to be able to sell large, expensive paintings that put it down. If you could, we'd see more of them.

So few, if any, patrons would be even remotely interested in buying a large painting whose entire message centered around the idea that we shouldn't have sex, or that it's bad. If anything, in fact, the center panel of the painting makes the activity that's taking place looked pretty darn good; not all that sinful, at least. And the whole point of temptation is that it seems to be good, but draws us away from God. away from the spiritual, and into the sensual.

More detailed treatments of the various fruits seen in the bottom portion of the panel can be reviewed in the slide show for the center panel. Click here to return to the main page for other essays and the interpretive slide shows.

A Doremishock resource

Contact

All material copyright 2013 by Lee van Laer. This work may not be reproduced without permission.