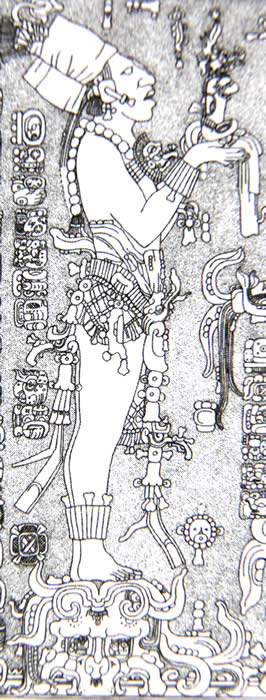

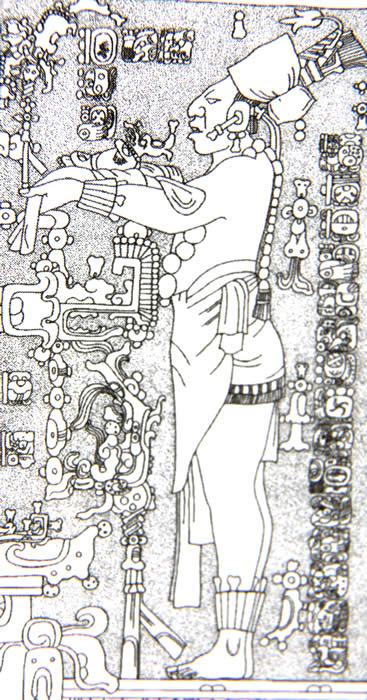

As is in the case with other esoteric systems, the man with smooth skin (like Jacob) has higher inner qualities—his being is inward. The man who who is clothed (like Esau, who was hairy) has lower or more outward qualities. The differences between the two are emphasized by the size of the figure — the men with smooth skin and less clothing are much larger — and the fact that the clothed figures are both lower down in the picture plane than the larger ones. In point of fact, the head of the left hand figure above breaks into the plane of the heavenly realms, while the one on the right does not. The visual treatment makes the relative spiritual rank of the two men quite clear.

Although these images express, on their surface, the ascension of the king from his younger self to his more authoritative coronated state, there is—as is so often the case where politics and religion are intimately mixed — a second and esoteric meaning. This is because kingship is so routinely intertwined with inidgenous religions. As at Angkor Wat and other major temple complexes around the world, the temporal and the spiritual are intentionally combined to confer authority on the temporal. Here, the Maya artists have had the foresight to functionally distinguish the two qualities—man's two natures, as it were—by keeping them on visually different levels.

In terms of their esoteric or mystical meaning, the allegories in the temples of the cross complex amply represent a familiar yogic principle: the growth of inner Being. The smaller figure holds devices that point downwards towards the earth; his orientation is material and of this level. The larger figures point upward, and offer figures of resurrection — creatures representing the birth of a new level of being — to the celestial bird. |

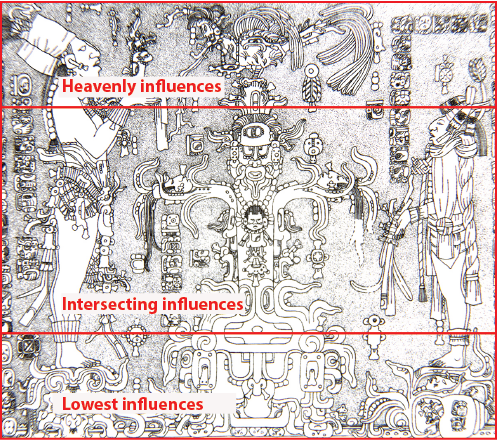

K'inich Janab Pakal's tomb cover, possibly one of the most aggressively misinterpreted pieces of artwork from the ancient world. Palenque.

This particular piece of esoteric art is a specific depiction of the resurrection of Pakal, who is shown supine in precisely the same position as the resurrection figure in the tablet of the cross.

He serves, here, as an offering to the Gods; receiving the energy of the cross as it flows down into the material world, and is shown rising upwards on currents of divine energy. In hindsight, perhaps, it's easy to understand why one might be tempted to see him as lying at the controls of a spaceship; he is, but this is a spiritual spaceship, a vehicle for ascent into the heavenly realms of inner Being.

|