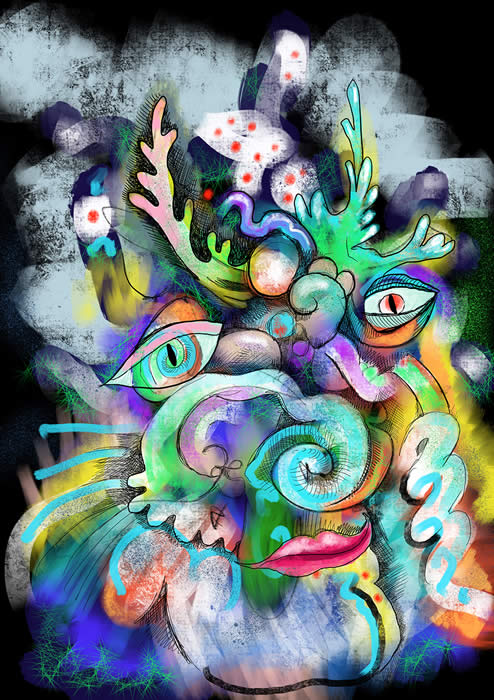

The mysterious beauty of unexplained natural phenomena

Lee van Laer, 2016

created on the iPad Pro using procreate

Worlds |

“Let us take some other word, for example, the term 'world.'

Each man understands

it in his own way, and each man in an entirely different way. Everyone when he hears or pronounces the word 'world' has associations entirely foreign and incomprehensible

to another. Every 'conception of the world,' every habitual form of thinking, carries

with it its own associations, its own ideas.

"In a man with a religious conception of the world, a Christian, the word 'world'

will call up a whole series of religious ideas, will necessarily become connected with

the idea of God, with the idea of the creation of the world or the end of the world, or

of the 'sinful' world, and so on.

"For a follower of the Vedantic philosophy the world before anything else will be

illusion, 'Maya.'

"A theosophist will think of the different 'planes,' the physical, the astral, the

mental, and so on.

"A spiritualist will think of the world 'beyond,' the world of spirits.

"A physicist will look upon the world from the point of view of the structure of

matter; it will be a world of molecules or atoms, or electrons.

"For the astronomer the world will be a world of stars and nebulae.

"And so on and so on...

"People have thousands of different ideas about the world but not one general idea

which would enable them to understand one another and to determine at once from

what point of view they desire to regard the world.

"It is impossible to study a system of the universe without studying man. At the same time it is impossible to study man without studying the universe. Man is an image of the world. He was created by the same laws which created the whole of the world. By knowing and understanding himself he will know and understand the whole world, all the laws that create and govern the world..."

"In relation to the term 'world' it is necessary to understand from the very outset

that there are many worlds, and that we live not in one world, but in several worlds.

This is not readily understood because in ordinary language the term 'world' is

generally used in the singular. And if the plural 'worlds' is used it is merely to

emphasize, as it were, the same idea, or to express the idea of various worlds existing

parallel to one another. Our language does not have the idea of worlds contained one

within another. And yet the idea that we live in different worlds precisely implies

worlds contained one within another to which we stand in different relations.

"If we desire an answer to the question what is the world or worlds in

which we live, we must first of all ask ourselves what it is that we may call 'world' in

the most intimate and immediate relation to us.

"To this we may answer that we often give the name of 'world' to the world of

people, to humanity, in which we live, of which we form part. But humanity forms an

inseparable part of organic life on earth, therefore it would be right to say that the

world nearest to us is organic life on earth, the world of plants, animals, and men.

"But organic life is also in the world. What then is 'world' for organic life?

"To this we can answer that for organic life our planet the earth is 'world.'

"But the earth is also in the world. What then is 'world' for the earth?

" 'World' for the earth is the planetary world of the solar system, of which it forms a part.

"What is 'world' for all the planets taken together? The sun, or the sphere of the

sun's influence, or the solar system, of which the planets form a part.

"For the sun, in its turn, 'world' is our world of stars, or the Milky Way, an

accumulation of a vast number of solar systems.

"Furthermore, from an astronomical point of view, it is quite possible to presume a

multitude of worlds existing at enormous distances from one another in the space of

'all worlds.' These worlds taken together will be 'world' for the Milky Way.

"Further, passing to philosophical conclusions, we may say that 'all worlds' must form some, for us, incomprehensible and unknown Whole or One (as an apple is one). This Whole, or One, or All, which may be called the 'Absolute,' or the 'Independent' because, including everything within itself, it is not dependent upon anything, is 'world' for 'all worlds.' Logically it is quite possible to think of a state of things where All forms one single Whole. Such a whole will certainly be the Absolute, which means the Independent, because it, that is, the All, is infinite and indivisible.

"The Absolute, that is, the state of things when the All constitutes one Whole, is, as

it were, the primordial state of things, out of which, by division and differentiation,

arises the diversity of the phenomena observed by us.

"Man lives in all these worlds but in different ways.

"This means that he is first of all influenced by the nearest world, the one

immediate to him, of which he forms a part. Worlds further away also influence man,

directly as well as through other intermediate worlds, but their action is diminished in

proportion to their remoteness or to the increase in the difference between them and

man. As will be seen later, the direct influence of the Absolute does not reach man.

But the influence of the next world and the influence of the star world are already

perfectly clear in the life of man, although they are certainly unknown to science."

With this G. ended the lecture.

Excerpts taken from In Search of the Miraculous by P. D. Ouspensky, pub. Paul H. Crompton Ltd, 2004, p72-76.